This document was made by OCR

from a scan of the technical report. It has not been edited or proofread and is

not meant for human consumption, but only for search engines. To see the

scanned original, replace OCR.htm with Abstract.htm or Abstract.html in the URL

that got you here.

ALTO

ALTO

USER'S

HANDBOOK

OCTOBER 1976

This

document is for Xerox internal use only

XEROX

PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER

OCTOBER

1976

This document is for Xerox internal use only

Table of Contents

Preface

Alto Non-programmer's Guide 1

Bravo Manual 27

Markup User's Manual 59

Draw Manual 73

DDS Reference

Manual 103

FTP Reference Manual 115

Preface

This

handbook contains documentation for all the standard Alto services intended for

use by non-programmers. It is divided into six sections,

separated by heavy black dividers:

The

Alto Non-programmer's Guide, which

has most of the general information a non-programmer needs.

The

Bravo manual,

which tells you how to deal with documents containing text on the

Alto.

The Markup

and Draw manuals,

which tell you how to add illustrations to documents.

Section 10 of the Non-programmer's Guide is an overview on illustrations.

Finally, two reference manuals, one for the DDS filing

service, and one for the FTP service which transports files between

machines. These manuals supplement the introductory information on

these two services in the Non-programmer's Guide.

If you are new to the Alto, start at the beginning of the

Non-programmer's Guide. Read the first four sections there, and then the first

two sections of the Bravo manual. After that, you should be able

to find what you need by looking at the tables of contents, and browsing

through the rest of the material. If you have trouble, don't hesitate to ask an

expert for help.

ALTO

ALTO

NON-PROGRAMMER'S

GUIDE

by BUTLER W. LAMPSON

Alto Non-programmer's Guide

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction 2

2.

Getting started 2

3.

The Executive 5

3.1 Correcting

typing errors 5

3.2 Starting

a service 5

3.3 Aborting 5

4.

Files 6

4.1 Naming

conventions 6

4.2 File

name patterns 6

5.

Recovering from disasters 8

5.1 Reporting

problems 9

6.

Keeping up to date 10

7.

More about files 11

7.1 Version

numbers 11

7.2 DDS 11

7.3 Copy 13

7.4 Dump and Load 13

7.5 CopyDisk 14

8.

Communicating with Maxc 15

8.1 Chat 15

8.2 About Maxc 16

8.3 Maxc

files 16

8.4 Hardcopy on Maxc 17

8.5 Archiving 18

8.6 Messages 18

9.

File transfers 21

10.

Pictures 23

11. Documentation

and software distribution 25

1. Introduction

This document is intended to tell you what you need to

know to create, edit and print text and pictures on the Alto.

It doesn't assume that you know anything about Altos, Maxc or any

of the other facilities at Parc.

You will find that things are a lot clearer (I hope) if

you try to learn by doing. This

is especially true when you are learning to use any of the

services which use the display. Try out the things described

here as you read.

Material in small type, like this

paragraph, deals with fine points which can be skipped on first reading (and perhaps on subsequent readings as

well).

I

would appreciate comments on this guide. In particular, I would like to know

what you found to be confusing or unclear, as well as anything

which you found to be simply wrong.

2.

Getting started

To do anything with an Alto, you must have a disk pack.

This is a circular, yellow or white object about 15

inches in diameter and 2 inches high. Your secretary can tell you how

to obtain a new one from the stock kept by your organization. The most common source

is the yellow cabinet in the Maxc room (room 1153 on the first floor). Go

straight through the first room, and you will find the

cabinet in the second room, in the far left corner. When you

take a disk, be sure to write your name on the logging form provided for

the purpose, together with the serial number of the disk pack, which you will

find on its bottom.

INITIALIZE

YOUR DISK

The next step is to get the disk initialized with copies of all

the programs you will need to use. Here is how to do this:

Go to the first Maxc room (room 1153 on the first floor;

this is the room you just went through to get your disk

pack). There you will find a rack containing (among other things) a

disk pack labeled BASIC

NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK, and an Alto which has two disk drives,

each with four square lights, a white switch and a slanted plastic

window. Take this BASIC

NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK and load it into the drive labeled 0. You do

this as follows:

The drive should have the white switch in the LOAD

position, and the white LOAD light should be lit. Open the

door by pulling down on the handle. Put in the disk by holding

it flat, with the label facing you, and pushing it gently into the

drive until it stops. Then gently close the door and push the white switch to

RUN. The white LOAD light will go out, and after about a

minute the yellow RUN light will go on. The disk is now loaded and ready to go.

If anything else happens, you need help.

Now start the Alto. This is done by pushing the small

button on the back side of the keyboard, near the thick

black cable. Pushing this button is called booting the Alto. It resets the machine

completely, and starts it up working on the disk you have just loaded. After

you boot the machine, it will tell you at the top of the screen what it thinks

the state of its world is, and then it will print a

">" about halfway down the screen. When the screen

looks like that, anything you type will be read by the Executive, whose basic

job is

to start up the service you want to run. There is a

section on the Executive later in this document.

For now, you will find everything you need to know right here.

You

are going to use a service called CopyDisk, which copies everything on the main

disk (which you just loaded) onto

another disk which you will load into the disk drive labeled 1. This copying erases anything which is already

on the disk in disk drive 1, so you should be very careful not to copy onto a disk which has anything you want to

keep. Load your new

disk into the disk drive labeled 1, doing just what you did to load the BASIC

NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK into drive 0.

Now type

>Copy DiskC3.

The CR

stands for the carriage RETURN key on the keyboard. In this and later examples, what you type is underlined in the example, and

what the Alto types is not.. On the screen, of course, there won't be any underlining. It doesn't matter whether you

capitalize letters or not;

the capitalization in this manual is chosen to make reading

easier.

The CopyDisk service will start up and ask you some

questions, which you answer as follows:

Copy from: DP0a the digit zero, not the letter 0

Copy to: DP1CL

Check after copying: Yes

Copy from DPO to DP1 with checking on [ confirm ] Yes

Now

CopyDisk will copy the contents of the BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK onto your new disk pack. This takes about two

minutes. While it is running, it records its progress in the two numbers near the top of the screen: they have to count up to 406

twice. When it is done, it will

ask you "Do you want to make another copy of the original disk?"

Answer No, and CopyDisk will return

to the Executive, which will type its ">" character, meaning that it is waiting for further instructions.

Now you

can take both disks out of the machine. Before you do, you should tell the Executive that you are finished, by

typing

>0u4CR

You

will see that after a couple of seconds the screen goes blank and starts to

display a white square that

jumps around. This is an indication that the memory test program

is running properly; an Alto

should always be left in this state when it is not being used.

Now

take out both disks, by pushing the white switch on each drive to LOAD. The

yellow READY light should go out,

and about 25 seconds later the white LOAD light should go on. Now you can open the door (aeainst a slight resistance) and remove the disk. Put the

BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK back in the rack where you found it.

If the

Alto in room 1153 is broken or unavailable, you can do a CopyDisk from one standard Alto to another; the procedure for doing

this is described in section 7.5. Since it is a little more complicated than the method just given, a novice should

use it only as a last resort.

LABEL

YOUR DISK

Before

doing anything else, put a label on the new disk with your name, and

any other identifying

information you like. Now you can take the new disk to any Alto, load it in, boot the machine by pushing the button on the

back of the keyboard, and start working.

NAME YOUR DISK

When

you do this, if you look at the information printed at the top of the screen

just after you do the boot, you will see that it says

--- OS Version x/x --- Alto #xxx --- NoName --- Basic

Non-programmer's Disk --‑

This is because your new disk is an exact copy of the BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK, which

has no owner, and owner and disk name information got copied along with everything

else. To give the disk your own name as owner, you should type

>Installa

to

the Executive. It will ask you whether you want the "long installation

dialogue"; answer No. When it asks you for your name, type in your Maxc

account name, followed by a CR. When

it asks you for a disk name, choose a suitable one and type that in, again

followed by a CR. Next

it will ask you whether you want to give your disk a password. If you do this, the Alto will ask you for

the password every time you boot it, and won't let you do anything until you

provide

it correctly. This provides

a modest level of security for the information on your disk. If you do give

your disk a password, it is best

to use your Maxc password, since the Alto will then know it and use it

automatically whenever you

communicate with Maxc. Don't forget the password, since there Js no simple way

to find out what it

is, and you will need an expert to get access to anything on your disk.

There will be a pause for a few seconds, and then the Executive

will come back (If you assigned a password to your disk, you will be asked for it

first). Now your name is installed on the disk, and the system

will display it near the top of the screen whenever the Executive is in control,

and will put it on the cover page of anything you print.

3. The Executive

This is the service to which you are typing right after a

boot, and whenever any other service finishes its job.

It has two display areas on the screen, a small one of six lines at the

top, and a large one of about 20 lines in the middle. When you are talking to

it, your typing and its responses appear in the large area.

Whenever you call another service, the large area is erased, and the command

you gave to call the other service appears at the bottom

of the small area. In between the two areas, the Executive displays a clock and

some other useful status information: the versions of the

Executive and the operating system, the owner name and disk name installed on

the disk, and the serial number of the Alto you are using.

3.1 Correcting typing errors

When you are typing at the Executive and you make a

mistake, there are a few special keys you can type to correct the mistake. The BS (backspace) key

erases the last character you typed. The DEL key cancels the

command you were typing completely; it prints "XXX", and

then starts a new line with a fresh ">" character.

3.2 Starting a service

As

we said before, the Executive is for starting up other services which do the

work you want done. To start a service called Alpha, you just type

>Al phagi

It doesn't matter whether you type in capitals, lower

case, or a mixture of the two. If the service needs some other

information about what to do, you type that after the name of the service.

For example, there is a service to type out a document on the screen. Suppose

you want to type out the document called "Notes". You just say

>Type Notes

The

Executive won't ever do anything until you type the final CR; if you change your

mind, just type DEL to cancel the command any time before you type the CR.

3.3 Aborting

You can usually stop what is going

on and get back to the Executive by holding down the left-hand SHIFT key and striking the blank key in the lower right

corner of the keyboard (called the SW AT key; on an Alto 2 it's in the upper right

corner). If this doesn't work, you can push the

boot button.

If you push the SWAT

key while holding down both CTRL and SHIFT, you will find yourself talking to a

service called Swat

which is of no interest to non-programmers. Usually no harm is done if this

happens; you can get

back to what you were doing before by typing PC (control-P; hold

down the CTRL key and type P).

4. Files

The Alto stores on your disk all of the material

you are working on (text and pictures), as well as all the

programs which provide the various services described here. The named unit of

storage on the disk is called a file.

Each different document you handle will be stored on

its own file. The facilities for identifying files are not ideal, but you will

get used to them after a while. Better facilities are the subject of

current research.

A file is identified by its name, which is a string of

letters (upper and lower case can be used interchangeably), digits,

and any of the punctuation characters "+-.!$". A file name can

have two parts, which are called the main name and the extension., they are separated by

a period. For example, "Alto.Manual" is a file name, with main name

"Alto" and extension "Manual". File names cannot

have blanks in them, or any punctuation characters except the ones just

mentioned. A file name must not have more than 39 characters; most people

don't notice this restriction.

A file name can also have a version number, which

is a number that comes at the end of the name, preceded by an exclamation

point: for example, "Alto.Manual!4" is version 4 of the

file Alto.Manual. Version numbers are discussed in detail in

section 7.

4.1 Naming

conventions

It is important to name your files in some systematic way,

using the extension to tell what kind of file it is, and the

main name to identify it. For instance, useful extensions might be

Memo, Letter, Note, Figure, Calendar. If you are a secretary keeping material

for several people on one disk, you can stick the person's

initials in front of the extension, e.g. BWLmemo, JGMmemo etc. If

you don't have anything specific in mind, it is customary to make

the extension the same as the name of the service which creates the file, e.g.

Report.bravo for a document which doesn't have

any special properties,

and is written

using Bravo.

The Alto doesn't care whether you capitalize

letters in file names or not (i.e. ALPHA and alpha and aLpHa

refer to the same file), but it is a good idea to use capitalization to make names

more readable. This is

especially useful when a name consists of more than one

word, since blanks are not allowed in file names: e.g.,

TripReport or MasterList.

4.2 File name

patterns

The Executive provides some simple facilities for

handling files. First of all, it allows you to name a group

of files by using file name patterns

containing the magic characters

"*" and "#". The "*" character

stands for any string of characters. For example, the pattern

"*.memo*"

stands for all the files which have the extension "memo", and the

pattern "*.BWL*" stands for all the files which have BWL as the first

three characters of the extension. The "#" stands for any

single character; for instance, "###.memo" stands for all

the files which have a three character main name and the extension

"memo". If you are

curious to see what a pattern expands into, you can type Xc to get it expanded.

If

you type a file name or a pattern to the Executive, and then type a TAB,

it will give you a list of all the files whose names start with that name. So,

for example, typing

>*.BwiTAB

will get you a list of all files which have an extension

starting with the characters BWL. You can get other kinds of lists

of file names using the DDS service described later, but this is

a useful quick and dirty facility.

Another useful thing to know is this: if you are in the

process of typing a file name to the Executive, and you type ESC, it

will add as many characters as it can to complete a file name.

If you type "T', it will give you a list of all the files which start with

what you have already typed; you can then go on and finish the

file name.

Here

is a summary of magic characters for getting file names expanded:

ESC completes the file name if possible; if not, completes as

much as it can, and flashes the

screen.

TAB shows

you all the file names which match what you have typed since the last blank,

and

erases what you typed.

like

TAB, but doesn't erase anything.

Xc retypes the command line with all

file name patterns replaced by the list of file names they

expand to.

There

are two mme simple commands for dealing with files. To delete a file, or a

group of files, type

>Delete Fl F2 ..CR

Warning: once

you have deleted a file, you cannot get it back. Proceed with caution. If there

is more than one version of a file, the one with the lowest version number gets

deleted.

To get the contents of a text file printed on the screen,

type

>Tvpe

If

the contents won't fit on the display, the Alto will show you as much as will

fit, then ask if you want to see more. If you do, just type a space; if you

want to stop, type "n" for no.

When the Executive is running, it displays two lines of

status information near the top of the screen. Included in

this information is the amount of space which is left for storing files.

This space is measured in disk

pages; it takes about 5 disk pages to store one page of text.

It is prudent to keep at least 150 disk pages available; if your disk has

fewer, you should delete some files, perhaps after sending them to

Maxc for archiving (see sections 8.5 and 9).

At this point you

know enough to use Bravo to begin creating and editing text. Bravo is described in its own

manual. You should start reading the Bravo manual, and not try to continue with this guide

until you have become familiar with the material in the first two sections of the Bravo

manual. The

remainder of this guide contains more information about the Alto which you won't need on the first day,

but will probably want in the first week.

5.

Recovering from disasters

There are various ways in which your Alto disk can become

damaged. If this does happen, the procedures described in

this section will almost always allow you to recover the disk, or at

worst will let you copy files from the sick disk to a healthy one. It is

probably a good idea to get some help with this if you are not

experienced.

Here are the symptoms of trouble:

You can't boot the disk and get to the Executive.

You are out of disk space, but you think you should have

plenty; in other words, some disk space has

apparently gotten lost.

You

get an error message from some service which says something about disk errors or

file errors, and perhaps recommends that you should run the Scavenger.

You

hear a funny buzzing noise from the disk for a couple of seconds, after which the

service you are using breaks in some way.

It may be that the

problem is caused by an incompatibility between the disk drive on which your

disk pack was written,

and the disk drive on which you are trying to use it. This is a likely cause of

your problems only if you have been moving the pack from one machine to

another, and if you notice that it works properly on some machines, but not on others.

If your problem is caused by disk incompatibility, the procedures described below won't do you much eood.

Instead, you should report the problem to the hardware maintenance staff, so

that the offending disk drive can be realigned, and make yourself a new disk

pack on a machine known to be in alignment_ You can transfer files from the old pack to the new one

using the procedure described in section 6.

The first step is to run a service called Scavenger. If your disk is healthy enough to let you

boot and use the Executive, you can just invoke the

Scavenger by typing

>Scavengera

If

it isn't, you can hold down the BS key

and the top two blank keys, and press the boot button (keep the keys

down until you see a fuzzy cursor in the center of the screen; this can

take up to 5 seconds). This will get you a copy of the Scavenger

over the Ethernet; after the cursor appears, it takes about 15

seconds more for the procedure to complete. If this doesn't work,

hold down just the BS key

and press the boot button; this should give you the dancing white

square of the memory diagnostic. If it doesn't, either your Alto's Ethernet

connection is broken, or your Alto has not been updated with the latest microcode

(the latter is unlikely after 1/1/77). Either find

another Alto without these problems, or load in a disk which is

still in good shape, invoke the Scavenger, and then unload the good disk and

load your sick one. The Scavenger will ask you whether you want to change

disks, and give you a chance to do so if you say yes. Then it

will ask you if it can alter your disk to correct errors; say yes.

The

Scavenger will now work for about a minute. As it runs, it may ask you whether

it is OK to correct "read errors". If they are

"transient" errors, answer Yes fearlessly; if they are "permanent"

errors, it is best to ask for advice from an expert. When the Scavenger is

done, it will tell you what it found. If it has succeeded in making your disk

healthy, you can go about your work. If it has deleted some

files whose contents you value, read the description of Extract

below. After you have retrieved anything which interests you from the

debris, delete the file Garbage.$ which the Scavenger leaves around. It is a

good idea to go through this scavenging procedure once a

month or so, just to keep your disk in good shape.

If things are still in

bad shape (i.e., you can't boot and run the Executive), the next step is to

boot again, this time

with the BS key and the top blank key held down. This should get you a fresh

copy of the operating system,

which will ask you whether you want to Install. You should say Yes, and go

through the Install procedure

described in section 2. If all goes well, you will then find yourself talking

to the Executive and can proceed normally.

If this doesn't work,

there is one more step to try. Boot again, this time with BS and the middle

blank key held down. This

should get you the FTP service described in section 9; use it to transfer the

files <Alto>Executive.run

and <Alto>SysFontal from Maxc. Then boot the Scavenger as described above

and run it again. If

this fails, you should consult an expert. If no expert is available, you can

boot FTP again, and use it to transfer files from your broken disk to Maxc or to a clean disk on

another Alto (made using the procedure described in section 2).

The Scavenger leaves

all the stuff which it wasn't able to put into a recognizable file on a file

called Garbage.$,

and it leaves a readable record of everything it did on another file

called ScavengerLog (unless it tells you that you have a beautiful disk). There

are two kinds of entries in ScavengerLog: names of files removed from the directory or

otherwise modified, and names of file paees which were put into Garbage.$. Such pages are identified by the serial number of the file, the page number of

the page, and the number of the page in the Garbage.$ file. The other ScavengerLog

entries allow you to find the serial number of a file which was smashed; the serial

number is printed as two or three numbers

separated by semi-colons.

To retrieve some pages from a

smashed file called Alpha, first look in ScavengerLog to find Alpha's serial number. Then look for a group of

pages with that serial number which were moved to Garbage.$. Make a note of the page number p in Garbage.$ of the first such page, and the number of pages a. Then type:

CR

>Extract Alpha p n--

and the desired pages will show up on Alpha. If it

was a text file, you can now start Bravo, Get it in, and see what you can make of it.

5.1 Reporting problems

If

your Alto itself is broken, obtain a trouble report form, fill it out, and

leave it in the proper place; procedures for doing this depend

on your location.

If

you have trouble with Bravo, report it using the procedure in section 4.3 of

the Bravo manual.

For other problems, consult your local expert.

lO ALTO

NON-PROGRAMMER'S GUIDE

6. Keeping up to date

When new versions of

the various services are released, they are normally announced by Maxc messages

to all registered Alto users (see section 8.6). You can obtain a new version of a service called Alpha as

follows:

Using FTP, attempt to retrieve <Alto>Alpha.cm. If this

succeeds, leave FTP and type to the Executive

>@Alpha.cm@fik

This will cause FTP to be invoked again, some files to be transferred

from Maxc, and perhaps

some other activity. When everything settles down, you will-have the new version.

If there is no <Alto>Alpha.cm, retrieve <Alto>Alpha.run. This

will be the new

version of the service. You don't have to do

anything else.

The best way to obtain a complete

set of new software, and clean up your disk at the same time, is to obtain a fresh disk, initialize it from the BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK as described in section 2, and then copy the files you want to keep from

your old disk to the new one. To do this,

put the new disk in an Alto and start the FTP

service (section 9.).

Note the Alto's serial number,

in the top right corner of the screen. Then put the old disk in another Alto, and use DDS (section 5.1) to mark all the files you want to

keep. When you have done this, use the DDS Send to command, giving it the number of the Alto with the new disk in it, followed by a

#: e.g., 236# (you can use the name instead, if you know it). This will call in FTP and start it sending over all the marked files to

the new Alto.

An

alternative way to make a BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK is to put the disk you want to initialize into an Alto, hold down the BS key and the top blank key, and push to boot button, as described in section

5. YOu will get a fresh version of the operating system, which will ask you if you want to

Install. Say yes, ask for the "long installation dialogue", and say that you want to erase a

disk. After a minute or so, you will have a clean disk with nothing on it except the

Executive and FTP. Use FTP to retrieve the files

<Alto>NewNpDisk.cm. Then

type

>@,NewNoDisk.cm@

This will automatically transfer

all the needed files from Maxc, and do any other necessary initialization. It takes about 20

minutes, and puts a significant load on Maxc, so use this procedure only when you can't

find the BASIC

NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK. During the operation,

there will be an automatic Install of the operating system; answer its

questions appropriately.

There will also be an automatic initialization of Bravo, and you should do a Quit when it is finished.

7. More

about files

This section describes various things you will need to

know about the Alto filing system.

7.1 Version numbers

A file name normally has a version number, which

is a number that comes at the end of the name, preceded by an

exclamation point: for example, "Alto.Manual!4" is version 4 of the file

Alto.Manual. The basic rule for version numbers is this:

When you read a file, you get the one with the largest

version number (the current version),

unless you include the version number you want in the file

name.

When you write onto a file for which the current

version is n, a

new version n+1 is created, and becomes the current version, unless

you include the version number in the file name. Furthermore, if version n-1

was around, it gets deleted, so that just two versions of the file are

kept, the current one (with the largest version number)

and the next

earlier version.

For example, if version 4 is the current version

of the file Alto.Manual, there will probably be

"Alto.Manuall4" and "Alto.Manual!3" around. If you write

onto ''Alto.Manual" (e.g. by doing a Put from Bravo),

"AltoManual!3" will disappear, and "Alto.Manuall5" will

appear with the new information on it. "Alto.Manual!4"

will still be around unchanged, so you can get the old version back from there

if you need it. On the other hand, if you write onto

"Alto.Manual!4", that file will be changed, and no new versions will

be created.

If a file name doesn't have a version number, most

services will not make any new versions, but will just

write on the single version. Bravo is an exception; it always makes new

versions, unless you have turned off versions at Install time, If you don't like

the version feature, you can turn it off when you Install, by

asking for the "long installation dialogue" and answering the

questions appropriately. You can also change the number of versions

which are kept in this way.

7.2 DDS

There is a service called DDS which allows you to keep

track of your files and do various useful things

with them. It is very easy to use, since most of the commands are self-explanatory.

Be sure to start it up before going on with this section, and try out the various

facilities as they are described.

Like

Bravo, DDS needs

to be initialized whenever

you run the Scavenger, change your user profile, or find that it

isn't behaving well. You do this just as for Bravo, by typing

>DDS/icR

to the Executive when you call it. DDS takes about 12

seconds to start up normally, and about 30 seconds if you are

initializing it. Unlike Bravo, Dos remembers its state, and restores

the previous state whenever you start it. You can also use initialization to

force it back to the original initial state. To get out of DDs,

point at the word Quit in the upper left corner of the screen

and click YELLOW. Or

you can just type SHIFT-SWAT.

Whenever Dos is doing something, and not

listening to the keyboard, it displays an hourglass in the cursor.

When you see the hourglass, you shouldn't expect any response to

your actions:

wait until it goes

away.

The

DDS screen

is divided into four windows. From top to bottom, they are: a command window, a control window, a filter window and a file window, which are separated

by horizontal lines across the screen. The file window, at

the bottom of the screen, is a Bravo-style window in

which DDS will tell you various things

about your files. The control and command windows contain menus: if you point to a menu word

and click a mouse button, something suggested by that word will be

done.

The bottom window starts out with a list of your files,

which are initially sorted by the time they were written. This

window has a scroll bar exactly like Bravo's. When the cursor isn't

in the scroll bar, you can use it to select or mark files; commands like delete

work on the marked files. The RED (left or top) mouse button marks a file, and BLUE (right or bottom) unmarks

it. Marked files are displayed with an arrow in the left margin. If you hold down

the button and move the cursor around (not too fast), all the files it passes

over will be marked (or unmarked). You can also mark or unmark all

the files which are displayed by moving the cursor to the

right until it turns into a box containing the word ALL, and

then using RED or BLUE.

Just

above the files is the filter window.

The two lines labeled Selspec and Context contain filters

which decide which file names to display. A simple filter is just like a file name

pattern in the Executive; it can include *'s and #'s, and it allows only file

names which match the pattern to be displayed. To see all the

files, you can just use * as the filter: note that the

Selspec is initialized that way. You can also type more complicated filters,

using and, or, not and parentheses: the Context is initialized to one

such complex filter.

The two filters act together, and a file name must

pass both of them to be displayed. The idea is that the Context can be used to

filter out a lot of things you almost never want to see,

and the Selspec can provide fine control. Note that the Context is

initialized to suppress all the standard system files.

To change a filter, point at the text of the filter with

RED. It

will turn black. Now type the new filter, which will replace the old one

as soon as you type the first character. End your typing with CR or ESC; the

latter appends a * to the filter. DDS will immediately update the file

window to reflect the new filter. If you type DEL instead, the old filter

will be restored.

Above the filter window is the control window, which contains a

list of sort words and

a list of show

words. If you select sort words (with RED) they

turn black and move to the left; you can unselect them with BLUE. Moving

the cursor down into the file window will get the list of files sorted

according to the sort words which are selected. Usually, you only want

to select one sort word. The YELLOW button reverses the direction of sorting (indicated

by the arrow next to the word) when it is clicked with the cursor over a sort word.

DDS is

initialized to sort on time written; that is why the sort word written is

black. Try turning written off (with BLUE) and

sorting on name. Now reverse the direction and sort again. Now turn off name and sort on extension.

The show words say what properties of the file will be

shown along with the name. You can turn options on with RED and off with BLUE, just

like sort words. The file display won't be updated until you

move the cursor down into the file window. The marked show word

limits the display to marked files. Note that DDS is initialized with written

and size (the number of disk pages in the file) turned

on. Try some other show words.

Finally. at the top is the command window. Commands act

on marked and filtered files only, and should be

self-explanatory. A command must be confirmed with ESC or CR before it

takes effect. Some commands take other parameters, which you should type before

the ESC or

CR. The

typing appears in a black region just above the commands;

sometimes

DDS will

supply a default value, which you can override by typing something else.

You can mark some files, and then change the filters so

that the marked files are no longer displayed; they will still

be marked. They will not, however, participate in a command. If you

later change the filters so that they are again displayed, they will still be marked,

and now they will participate in a command.

Here is an example which illustrates several features: it

deletes all the files whose names end in $ (these are usually

the files on which Bravo leaves old versions of files you have edited,

if you have file version numbers turned off). Point at the Selspec filter and

click

RED;

it will

turn black. Now type j* Ca; this will display all the

files whose names end with S. Now put the cursor in the file window, and

use RED in the

ALL bar

on the right to mark all the files. Finally,

select the delete

command and type ESC.

There are many options for initializing DDS. They

are all set up in a standard way in the user profile on the BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK, but

you can change them by editing the [DDS] section of the

file User.cm. Detailed instructions on how to do this can be found

in the DDS reference

manual, together with a lot of additional information about DDS itself.

This manual appears as DDS.ears on the Maxc <AltoDocs> directory (see section

11), and can also be found at the back of the Alto User's Handbook.

7.3

Copy

To copy one file to another, e.g., Old to New, say

>Copy New 4-

Old don't

leave out the spaces

The "4-" is to remind you of the direction the copying is

done.

7.4

Dump and Load

These services give you a way to package up a number of

files into a single, so-called dump file. You can then transport the

dump file around as a unit, and later recover one, a few, or all of the files

from it. This is especially useful when you want to send a group of files to

Maxc for storage or archiving.

To make a dump file, type

>Dump

alpha.dm fl f2

Here

"alpha.dm"

is the name of the dump file: by convention it has the extension

"dm." You can list as many files as you want to be dumped. Often the

* feature of the Executive is useful here.

To get files back from a dump file, type

>Load/v

You

will get a list of the files in alpha.dm. and after each one you will be

asked whether you want it loaded or not. If you leave out the

/v all the files which don't already exist will be loaded; if

you say /c instead, all the files will be loaded whether or not they are already

on your disk.

7.5 CopyDisk

The

simplest use of the CopyDisk service is copying the contents of one disk pack

to another on an Alto equipped

with two disk drives; it is described in section 2. CopyDisk can also copy the

contents of a disk pack from one Alto to another over the Ethernet. To use it in this mode, you need two Altos; in the

example below they are called Banjo and Flash. Put the disk you want to write onto into

one Alto (Flash), and start CopyDisk. If you want to copy onto a blank disk, which won't have an Executive and

therefore cannot be

booted from, you can start CopyDisk by holding down the BS

and ] keys, and pushing the boot button. After some delays, as described

in section 5. the CopyDisk service will be running.

The

first thing it does is to ask you "Copy from: ". Here you type the

name of the Alto from which you want to copy, followed by a CR.

If you don't know the name,

you can type the serial number

(displayed in the Executive"s status lines), followed by a #. The dialogue then proceeds as follows:

Copy from: Banjo

Copy to: DP0a- the digit zero, not the letter 0.

Check after copying: Yes

Copy from Banjo to DPO with checking on [ confirm ] Yes

Waiting on Ether ...

Next, go to the other Alto (Banjo), put in the disk you

want to copy, start CopyDisk and proceed as follows:

Copy from: DPO—

Copy to: Flash

Check after copying: Yes

Copy from DPO to Flash with checking on [ confirm Yes

Now the

copy should proceed. When it is done, the source Alto will ask "Do you

want to make another copy of the

original disk?". You can answer No, and it will return to the Executive. The target Alto will say

"Waiting on Ether ...". and you can boot it and say Quit to the Executive.

8.

Communicating with Maxc

Many uses of the Alto

require you to communicate with Parc's large shared computer, which is called Maxc. To make

any use of Maxc, you must first obtain a Maxc account and password; to do this, see the CSL laboratory

manager's secretary.

Before trying to use

Maxc from your Alto, you should first tell the Alto your Maxc account name and password. If you have

given your Maxc account name to Install as the owner name for your disk, however, the

Alto already knows it, and if you gave your Maxc password as your disk password, it knows that too

and you can skip to section 8.1. Otherwise,

you can give the necessary information by typing to the Executive:

>Loginal

The Login service will now ask

you for your Maxc name and password. Type in each one in turn, ending each with a CR or space. Note that it assumes your Maxc acount

name is the same as

your disk owner name; if this is the case, you can just type CR to confirm it, and go on to give your password. If

it isn't, type DEL, and then give the Maxc name you want to use. Once you have done

this Login, your Alto will automatically identify you to Maxc whenever necessary. If you boot your Alto, it will forget this

information, and you must Login

again.

Note that the Login

service only records your Maxc name and password; it does not connect you to Maxc. If you don't do a Login, both Chat and FTP will

automatically ask

you for the Login

information when they first run, and will record it just as Login does.

If you wish, you can

supply a password for your disk when you Install (see section 2). If you do this, you will have to type the password whenever you boot the

Alto. but it will automatically

be used as your Maxc password, unless you override it with a Login command. The

password is stored on your disk in encrypted form, so that your Maxc password cannot readily by

compromised to someone who paws around on your Alto disk.

8.1 Chat

You

can use your Alto as a Maxc terminal through the Chat service. Just type >Chatfa

If all goes well, you will see

the message "Connected to :", followed by some numbers, at

the top of the

screen, and a message from Maxe at the bottom of the screen. If Chat

has trouble getting

connected to Maxc, it will tell you its problem after trying for a few seconds. This usually means that Maxc is broken; you

might try again in a few minutes.

If you have forgotten

to Login to your Alto, Chat will ask you for your Maxc name and password. It will then record

this information, just as though you had given it to Login, so that you won't have to supply it again unless you

boot the Alto.

When Maxc types more

than a screenful at you, it will pause after every screenful and "ring the bell", which

causes Chat to display a large DING at the top of the screen. After you have had a chance to read the screen, striking

any key on the keyboard will get Maxc

to

produce the next screenful. If you type ahead to Maxc, this

feature is suppressed.

Maxc has its own

Executive, and a large array of services called subsystems. The next few subsections contain enough information about how to use

Maxc to satisfy your routine needs.

Chat

keeps a record of your conversation with Maxc on a file called

Chat.scratchScript. You can read it with Bravo after a Chat session, just to see what happened, or

perhaps to copy things out of it into other files, print it, or whatever. There are two funny things about this file

which you need to know about

The file is not

erased when you start a new conversation. Instead, the typescript of the new conversation starts at the

beginning of the file and continues for as long as the conversation lasted. The

end of the conversation is marked by the characters <_> after which you

will see the remnants of

the previous conversation.

The

typescript file is only 20,000 characters long. If your

conversation is longer than that, the

typescript will wrap

around to the beginning. It is possible to make the file larger by editing the

[CHAT] section of the user profile

(the file User.cm) in the

obvious way.

8.2 About

Maxc

Maxc has its own Executive and file

system, which are thoroughly documented in the Tenex Exec Manual. That manual was written primarily for programmers,

and contains a large amount of information

not needed by casual users of Maxc. In the hope of keeping you from having to read the Tenex Exec Manual, the

next few paragraphs contain a summary

of basic procedures for dealing with Maxc.

In order to do anything useful on

Maxc, you must be logged in. The details of this procedure will normally not concern you, since Chat

will take care of them automatically. When

you are finished with your Maxc session, however, you should log out by

giving the command

@Logoutak

to the Executive. (Note that Maxc types an

"@" when it is listening for commands, just

as the Alto types a ''>".) After a few seconds, you will get

a farewell message from Maxc. Then you can exit from Chat and get back to the Alto Executive by typing SHIFT-SWAT (hold down the left-hand shift key and hit the

blank key in the lower right corner of the keyboard).

If you expect to

use Maxc again within a few minutes, you can save a little time and some Maxc resources by not logging out. This

notifies Maxc that you expect to be back soon. If you don't return within a few minutes, Maxc will

log you out automatically. If you don't expect to be back soon, it is considerate to log out, since you use up

space on Maxc while you are logged in.

8.3 Maxc files

Maxc has a file system

somewhat like the Alto's, but the procedures for finding out about your

Maxc files are rather cumbersome. You will want to store files on Maxc for

several reasons (all of which

are explained in more detail below)

so

that other people can copy them easily, using the File Transfer service (see

9.);

so that others can obtain hardcopy easily, using

the Ears subsystem on Maxc (see 8.4);

so that they

can be archived on magnetic tape (see 8.5).

Maxc file names

look very much like Alto file names, but they have one more part: a directory.

Also, the version number is

always present, and is preceded by a semi-colon rather than an exclamation point.

The format is

<directory>name.extension;version

Each Maxc user has a directory, named by his Maxc user

name, and you can reference files in some other directory

simply by prefixing the directory name to the file name, as illustrated.

There is a protection system, not described here, which allows a user to

control which other users can read or write his files. The usual

setting of the protection, and the one you will get

automatically if you don't say anything special, allows all Xerox users to read

the file, but prevents anyone except the owner from writing it.

When you put a file onto Maxc, if there is already a file

with the same name, the new file is added, with a version

number one bigger than the old one, just as on the Alto when the file

version number feature is enabled. However, old versions are never deleted automatically.

When you reference a file, you get the one with the largest version number

if you don't specify the version explicitly,

just as on the Alto.

The ESC feature for

completing a file name works on Maxc more or less as it does on the Alto.

You can list the names of your Maxc files with

@Dirfa

If you want just the files with a particular main name or

extension, you can say

@Dir activitv.*gi or

@Dir *.reportCR

but

these are the only uses of * which will work. To list another user's directory,

say @Dir <user>fl

You can get more detailed information about your

files (length, date written, etc.) with

@Dir21 note the comma

@@vCR

@@CE

If

you want to print or otherwise manipulate this list, read the Chat typescript

into Bravo and treat it like any other

piece of

text.

You can delete one or several Maxc files, just as on the

Alto, with

@Del fl f2

and

*s will also work here, just as in the Dir subsystem described above. To delete

all the old versions of your files, say

@Delvergi

answer

the two questions Yes, and type a CR when you are asked for the "file

group." It is a

good idea to do this once a week or so, since old versions can pile up and

waste a lot of space.

To find out how much space you are using on

Maxc, type @Dskal

One

Maxc page is equivalent to about five Alto pages.

8.4 Hardcopy on Maxc

If you have a file, say TripReport.ears, in

"Ears" or "Press" format (see section 10 for an explanation

of these formats), i.e., ready for printing, you can get it printed by typing @Ears TripReporta

If you want 6

copies, say

@Ears

TrinRenort,a note the comma

@@Copies 6CL @@cji

This is mainly useful for printing files on other

directories, which other people have left there to make it convenient

for you to print them. If the extension isn't "ears", you have to

type it as part of the filename.

You can get Bravo to produce an Ears file by using the E

option in the Hardcopy command. You should give the file the extension

"ears." Then you can send it over to Maxc using the File

Transfer procedure described in section 9.

8.5 Archiving

Maxc provides facilities for archiving

files onto magnetic tape, where the cost of storing them

is negligible. You can get an archived file back within a day with no effort,

and within a few minutes at the cost of some inconvenience.

To

archive one or several files, type

@Arch f filel file2 ...--CR

The

files will be archived onto tape within a day or two. After this has been done,

they will be deleted from the disk automatically, and you will

get a message notifying you that the archiving has been

done.

Maxc keeps track of your archived files in an archive

directory which you can list exactly like

your regular Maxc directory, using the Interrogate command rather

than the Directory command. If the listing is of just one file, Maxc

will ask you whether or not you want it retrieved

from the tape. If you say yes, the file will appear on your disk within a day,

and you will get a message to that effect. If you need the

file right away, see Ed Taft or Ron Weaver.

8.6 Messages

You

can send and receive messages on Maxc using two subsystems called Sndmsg and

Msg. To send a message, type

@Sndmsc,C2

and

fill in the To:, Cc:, Subject: and Message: as they are requested. You can edit

the message with the following control characters; this

editing is rather clumsy, however, so you should type the message as carefully

as you can.

Ac to backspace one character (not BS, unfortunately)

Qc to delete a whole line

Rc to

retype the current line

Sc to

retype the whole item

DEL to

abort the whole thing

CR to

terminate everything except the Message

Zc to

terminate the Message.

After

Zc type a CR. Maxc will report success as it sends the message

to each destination. You can make a list of people on a file,

say Csl.msg, and send a message to all of them by

typing

BC CSI.MS2C-- as part of the To: or Cc: lists.

There is a set of useful destination lists on the

<Secretary> directory; they all have the extension "msg", so

you can get a list of them with

@Dir <secretary>*.msga

To

get on a distribution list, send a message to Jeanette Jenkins.

You

can copy a file, say Meeting.notes (perhaps prepared with Bravo, but don't use

any formatting, and put in carriage returns yourself, rather than relying on

Bravo's automatic

ones), into the message by typing Bc

F Meeting.notes-C1-1.

To read your mail, type @msgCR

Soon Maxc will type a summary of your newly arrived mail,

and then a <- symbol. Notice that the messages are

numbered. You are now talking to Ivlsg; it has a rather complicated command

language which you can learn about by typing "?" after the

<- symbol. Here is enough information to get by on.

To see message n, type

<-Type

message

To

see the next message, type LF; to see the previous message,

type BS. To

see the current message again,

type T ESC. If

you want to save the message, after it has been typed, Get the Chat

typescript into Bravo.

You

can delete a message by typing

ll_R

>Delete

message

The current message can be deleted with >Delete

message ESC

It is a good idea to delete messages after reading them,

unless they reflect pending business. By keeping your

message file short, you will find that Maxc responds much faster,

and also you will be able to get a quick summary of pending business by listing

the message headers (From:, Date:, Subject:). To do this,

type

<-Headers of messages MCR

where for M you can say

All messages

Not examined messages

From nameC-1

Subject texta CR

m-n‑

m-n‑

To answer the message you just typed out, type <-Answer

message ESC

It will ask you where to send the answer, and

you

It will ask you where to send the answer, and

you

From

to send the answer to the sender, with All to send the answer to

everyone who got

You can also get into Sndmsg from Msg by typing

<-SndmsgCLEi

When

you have finished sending the message, you will be talking to Msg again.

Finally, two useful things:

To

stop Msg in the middle of typing the response to any command, type Oc;

if it was waiting at the end of a page, you will also

have to strike another key.

To

exit from Msg, type: <-Exita

Every

now and then you should clear <-Move All messages

Every

now and then you should clear <-Move All messages

to file 8Dec75.msg.a [new file]

-C-ii using the current date in the file name

<-ExitCE.

@Arch

f 8Dec75.msga

You can always retrieve

the messages if you need them. If you do want to read messages from

a file like the one created with the Move just described, you can tell Msg to

read that file by typing

<-Read from file 8Dec75.msga [old

version]cg‑

9. File transfers

You can transfer files from one Alto to another, or from

an Alto to Maxc, using the File Transfer Program, or FTP for

short. Like DDS, this program has a fairly elaborate set of features,

which are described in its manual. You can print this manual from <AltoDocs>Ftp.ears,

and you will also find it at the end of the Alto User's Handbook. This

section tells you enough about FTP to take care of all ordinary needs.

After starting FTP, you will see three windows on the

screen; from top to bottom, they are the server window,

the user window,

and the Chat window.

Most interactions with FTP involve only the middle window; note the blinking

vertical bar there, which shows where you can type. The first

step is to type the name of the machine you want to talk to. Usually

this is Maxc, and you should just type

*Maxca

In a second or two

you should get back a response like

Maxc

Pup Ftp Server 1.06 30-Jun-76

When

Maxc is broken, there will be delay of about a minute, before FTP gives up; you

can give up sooner by striking the middle blank key (opposite

CR). If you want to talk to another Alto, you can type

its name, if you know it, or its number followed by a #:

*Banioak

*326#C-a

*326#C-a

A

similar message should come back. Before doing this, you should make sure that

the other Alto is running FTP, since your Alto will only wait

one minute for it. You can get a list of all the Alto 'owners,

names and numbers from the Maxc file <System>Pup-Network.txt.

Now

you can retrieve a

file from the remote machine (Maxc, or the other Alto), or store a

file into it. To retrieve, you type

*R

etrieve remote file Example as

local file Exampie_cR

As

in the Executive, you can just type enough of the command to identify it

uniquely, and then a space; unlike the executive, FTP

supplies the rest of the command name automatically. You then

type the Maxc (or remote Alto) file name, folowed by a space. FTP

will then suggest a local name for the file. If you like it, you can just type

CR. Otherwise, you can type some other name, as in the

following example:

*R

etrieve remote file Example as local file Dummy-C1-

During

the transfer, the cursor will flip its two black squares back and forth every

time it transfers a block of the file, so you can tell how it is

progressing from the frequency of flips.

To store a file on your local Alto into the remote

machine, you type

*S tore local file Example as

remote file Example-CB‑

or

*S

tore local file Example as remote file Dummy—

again

depending on whether or not you want to use a different name.

You can do as many Retrieve and Store commands as you

want. When you are done, type *p_uit

and

you will be back talking to the Executive.

If you are not logged in, and are talking to Maxc rather

than another Alto, FTP will ask you for your Maxc user

name and password when you do the first Retrieve or Store. Like Chat,

it will save the information so that you won't have to provide it again until

you boot the Alto.

If you intend to do a lot of

transfers to a Maxc directory other than your own, you can give the command

*Dir ectory OtherDira

to make <OtherDir>

the default directory for Maxc names; this saves typing <OtherDir> in front of each name. You can also do

*Con nect to directory OtherDir Password xxxxx2-

which works just like the Maxc Connect command. The password

is not displayed when you type it, of course.

You can get a list of the Maxc

files which match a file name pattern with the command *List

You can get a list of the Maxc

files which match a file name pattern with the command *List

which works just like the Maxc

Directory command. It is quite slow, however, and there is no way to interrupt it except to

SHIFT-SWAT out of FTP.

which works just like the Maxc

Directory command. It is quite slow, however, and there is no way to interrupt it except to

SHIFT-SWAT out of FTP.

At the bottom of the screen is the

Chat window, in which you can talk to Maxc exactly as you do with Chat. You can

move the cursor down into the Chat window by striking the bottom unmarked key

(the SWAT key); to

get back to the middle window, strike the middle unmarked key (on an Alto 2,

the highest and lowest

unmarked keys on the right,

respectively). In the Chat window, after typing Maxca,

you can Login to Maxc and do whatever you want. This window doesn't

offer all the conveniences of Chat itself, but at times it is nice to be able to switch very

quickly between transferring files and giving commands to Maxc.

When you start FTP on an Alto, it

is normally ready to act as a remote machine or server, in addition to accepting commands as described above. If you don't say

anything special, it will allow any other machine to retrieve files, and to store new

files, but not to overwrite an existing file. You can change these defaults by starting FTP with

Ftp/X

where X can be: Nothing to prevent

any such transfers; Protected to allow retrieving only, but no writing; Overwrite to allow an existing

file to be overwritten. Any server activity is reported in the server windown

at the top of the

screen.

10. Pictures

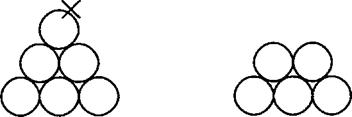

There are currently three major services for drawing

pictures on the Alto:

Markup: good for pictures involving images,

free-hand drawing or painting. Markup is also useful for

adding pictures to a text document produced by Bravo; these

pictures can come from Draw or Sil, or they can be drawn

by Markup itself.

Draw: good for pictures which just contain lines, curves and text;

Sil: good for forms and pictures with only

horizontal and vertical lines.

At the moment only the first two are suitable for general

use. Each has its own manual, copies of which can be

obtained by printing <AltoDocs>Markup.ears and Draw.ears (see section

8.4). You will also find these manuals in the Alto User's Handbook.

You can compose the various parts of a document with

Bravo, or with any of these picture-drawing services,

and then put together the complete document with a service called PressEdit.

This service can combine two kinds of files which describe pages of a document:

Press files

and Ears files.

Markup, Draw and Sil can all produce Press files, and

Bravo can produce Ears files. You will find an explanation of how to use

PressEdit in

the

next section. Warning. the

resulting Press file will be about as big as all the input files;

be sure you have enough disk space.

The

input to PressEdit must be a Press or Ears file. Markup automatically produces

Press files, but the other services require extra steps to make

the right kind of file for PressEdit.

For Bravo, use the Ears option on the Hardcopy command to

get an Ears file. This file will be on your Alto disk, like any other

file. If the Bravo file was named "Example.bravo",

the Ears file should be named "Example.ears".

For Draw, use the Press command to get a Press file.

For

Sil, use the Nppr service to get a Press file, which is always named

"Sil.press". You should rename it to something reasonable.

In all these cases, the resulting Press or

Ears file cannot be

converted back into Bravo, Draw or Sil form. You should therefore do all

the work you can in these systems before making a Press or Ears

file.

The output of PressEdit is

a Press file, and you can do the following things with it:

1) Print

it on the Ears printer from your Alto, by typing to the Executive >Print Example.pressCE

Currently this is done through Maxc, and takes a

while. if you type /s

immediately after a

file name, the file will be saved on your Maxc directory in Ears format. if you

type n/c before a file

name, n copies will be printed. Thus

>Print 5/c Example.press/.s

2) Send

it to Maxc with FTP, and then print it on the Ears printer by

typing

@Ears

Example.pressal

When doing this, you can make several copies if you wish,

as described in section 8.4. In addition, you will be asked if you

"want to save the Press conversion?" You should

do this if you expect that a number of other people will want to print the file

later, since it requires quite a lot of Maxc resources to print a Press file.

If you do save the Press conversion, you will be asked for a

file name; choose the name Example.ears if the Press file was

Example.press. The resulting Ears file can then be printed by

typing

@Ears Example.earsat

with much less Maxc computing. If you save the

Ears file, you should delete or archive the Press file, so

as not to consume too much Maxc file space. Note: you can also save the Ears file

with the Print

service, as described earlier.

3) Send

it to the 3100 Alto in room 2064 and print it on the 3100 there. The advantage

of doing this is that pictures made by Draw will be much prettier; the drawback

is that the 3100 is slower, and the procedure for printing is only semi-automatic.

To print on the 3100, you should start FTP on your Alto, go to the 3100

Alto, run FTP there,

and retrieve the Press file from your Alto. Then follow the

instructions in the notebook labeled Press to get your file printed.

4) Look

at it with Markup, and possibly make changes. Read the Markup manual to find

out how to do this. You can make substantial changes to the document with Markup,

but the procedure is rather laborious, and you cannot transfer any of the changes

back to the Bravo, Draw or Sil files you started with. Therefore, it is best to

get all the pieces of the document into final form before assembling it and marking

it up.

The use of PressEdit for assembling

documents has one major advantage: the resulting complete document

can be left of Maxc for printing by anyone who needs a copy. If you are

producing a document for large-scale printing outside, on the other

hand, it is probably easier to assemble it by hand than to go through all this ritual.

10.1 PressEdit

To convert an Ears file foo.ears to a Press file foo.press:

>PressEdit

foo.press F foo.earsa

To extract pages 3 and 17 from a Press file long.press, and put them in

short.press:

>PressEdit

short.press F long.press 3 17Cg

To extract pages 5 through 12 from foo.ears, and put them in short.press:

>PressEdit short.press 4- foo.ears

5 to 12CR

To add fonts Logo24 and Helvetical4 to a.press:

>PressEdit a.press a.press

Logo24/f Helvetical4/fLE

Here the arguments on the right hand side of the

arrow may be given in any order.

To

make a blank, one-page Press file containing all three faces of TiniesRontan10:

>PressEdit Bla nkTimes.press F Ti mesR oman 10/f TimesRomanl0i/f

TimesRoman 1 Ob/fgl

To

append to the end of chap3.press all the Press files with names fig3-1.press,

fig3-2.press, fig3-3.press etc:

>PressEdit chap3.press f

chap3.press fie3-*.presses

Cautiorr. when

you combine files with PressEdit, try not to use different sets of fonts, or the

same fonts in different orders. This will result in proliferation of font sets, making the

file more bulky and

creating other minor sources

of inefficiency.

11. Documentation

and software distribution

Documentation for all the

standard Alto software can be found on the Maxc <AltoDocs> directory. As a rule, each major

piece of documentation appears as an Ears file which can be printed by the Ears subsystem

on Maxc. Short documents are available on files with the extension "tty"; these

can be copied from Maxc to your Alto and read with Bravo, or they can be printed with

@Corw foo.tty

Ipt:cR [OK]

You can do

@Dir <AltoDocs>*.ears or *My

on Maxc to see what is available.

Current versions of all the

standard Alto software are stored on Maxc in the <Alto> directory. The procedures for

obtaining current versions are explained in section 6.

BRAVO

BRAVO

by BUTLER W. LAMPSON

Bravo Manual

Table of Contents

Preface 28

1. Introduction 29

2. Basic

features 31

2.1 Moving around 31

2.2 Changing the text 32

2.3 Filing and Hardcopy 34

2.4 Miscellaneous 36

3.

Formatting 37

3.1 Making pretty characters 37

Looks during typing

3.2 Paragraphs 38

Hints

3.3 Formatting style 41

Emphasis

Section

Headings

Leading Indenting Offsets

3.4 Forms 44

3.5 White space and tabs 44

3.6 Page formatting 45

Page numbers

Margins

Multiple-column

printing

Line numbers Headings

4.

Other things 50

4.1 Some useful features 50

4.2 Windows 51

4.3 If Bravo breaks 52

4.4 Arithmetic 53

4.5 Other useful features 54

Buffers

Partial

Substitution

Magnification

Control

characters

4.6 The user profile 56

4.7 Startup and quit macros 57

4.8 Diablo and Ears hardcopy 57

Samples of standard fonts

Preface

This manual describes the Bravo system for creating,

reading and changing text documents on the Alto. It is supposed to

be readable by people who do not have previous experience with

computers. You should read the first four sections of the Non-Programmers Guide to the

Alto before starting to read this manual.

You

will find that things are a lot clearer (I hope) if you try to learn by doing. Try

out the things described here as you read.

Material in small type, like this, deals

with fine points and may be skipped on first, or even second, reading.

I would appreciate any comments which occur to you while

trying to use the manual. In particular, I would like to

know what you found to be confusing or unclear, as well as anything

which you found to be simply wrong.

This manual is written on the assumption that you have the

user profile, fonts and other Bravo-related material from the BASIC NON-PROGRAMMER'S DISK. If

this is not the case, some of the things which depend on that stuff

will not work the same way.

There is a one-page summary of Bravo at the end of this manual. It is intended

as a memory-jogger, not as a complete specification

of how

all the commands work.

Bravo was designed by Butler Lampson and Charles Simonyi,

and implemented mainly by Tom Malloy, with substantial contributions from

Carol Hankins, Greg Kusnick, Kate Rosenbloom and Bob Shur.

1.

Introduction

Bravo is the standard Alto

system for creating, editing and printing documents containing text. It can handle formatted text, but it doesn't know

how to handle pictures or drawings; for

these you should use Draw, Markup

or Sil.

When

you start up Bravo (do it now, by saying Bravo/ea- to the

Executive), you will see two windows on the screen, separated by a heavy horizontal

bar. The top one contains three

lines with some useful introductory information; it is called the system window. The bottom one contains a copy of the material you are reading, which was

put there because of the

"/e" you typed to the Executive. If you had omitted the

"/e", as you do when using Bravo normally, the bottom window would be empty, except for a single

triangular endmark which indicates the end of a document. In the bar separating the two windows is the name of the document in the lower window.

As you do

things in Bravo, the first two lines of the system window will give you various

useful pieces of information which may help you to understand what is going on

and to decide what you should do next. Usually, the top line tells you what you

can do next, and the second line tells you what you just did, and whether

anything went wrong in doing it. Make a habit of looking at these

two lines while you are learning Bravo, and whenever you are unsure of what is happening.

No

matter what is going on in Bravo, you can stop it and get back to a neutral

state by hitting the DEL key. You can leave Bravo and get back to the

Executive by typing QuitCR

The

characters which you type (Q and CR) are underlined in this example; the characters which are not underlined are typed by Bravo. This

convention is used throughout the manual. Notice that you only type the first character of the Quit

command; this is true for all

the Bravo commands.

Each

Bravo window (except the top one) contains a document which you can read and change. Usually you read the document from a

file when you start Bravo, and write it back onto a file after you have finished changing it. Later,

you will find out how to do this (see section 2.3). It is possible to have several windows, each containing a

document; this too is explained

later on (see section 4.2).

Bravo

is controlled partly from the keyboard and partly from the mouse, the small white object with three black buttons

which sits to the right of the keyboard. As you push the mouse around on your working surface, a cursor moves around on the screen. Pushing the mouse to the left moves the cursor to the left,

pushing the mouse up (away from you) moves the cursor up; and so forth. You should practice

moving the mouse around so that the cursor moves to various parts of the screen.

The

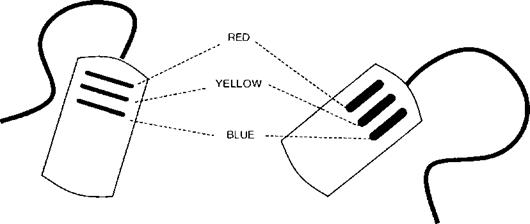

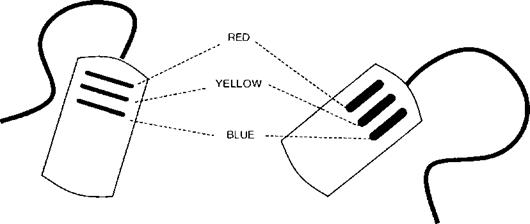

three buttons on the mouse are called RED (the top or left-most one, depending on what kind of mouse you have), YELLOW (the middle one) and BLUE (the bottom or right-most one). They have different functions

depending on where the cursor is on the

screen and what shape it

has. Don't

push any buttons yet.

Mouse lore:

You

will find that the mouse works better if you hold it so that it bears some of the weight of your hand.

If the cursor

doesn't move smoothly when the mouse is moving, try turning the mouse upside down and spinning the ball in the

middle with your finger until the cursor does move smoothly as the ball moves. If this doesn't help, your

mouse is

broken; get it fixed.

You

can pick the mouse up and move it over on your work surface if you find that

it. isn't positioned conveniently. For instance, if you find the mouse running

into the keyboard when you try to move the cursor to the left

edge of the screen, just pick the mouse up and set it down further to the

right.

2. Basic

features

This section describes the minimum set of things you

have to know in order to do any useful work with Bravo.

When you have finished this section, you can read the other parts of

the manual as you need the information.

2.1

Moving around

Move the cursor to the left edge of the screen

and a little bit below the heavy black bar. Notice that it appears

as a double-headed arrow. It will keep this shape as long as you stay near the

left edge, in a region called the scroll bar. if you move it too far right, the shape will

change. Keep the cursor

in the scroll bar for the moment.

Now push down the RED (top or left) button and hold it down.

Notice that the cursor changes to a heavy upward arrow. This indicates

that when you let the button go, the line opposite the cursor will be

moved to the top of the window. Try it. This is called scrolling the

document up.

Next push down the BLUE (bottom or right) button and hold it down. Now

the arrow points down, indicating that when you let the button go,

the top line on the screen will be moved down to where the

cursor is. Try it. This operation takes a few seconds, so don't get